This research article focuses on the maritime territorial and border disputes and negotiations taking place between the States of Lebanon and Israel. Negotiations and the dispute itself have intensified ever since oil and natural gas were discovered in the Eastern Mediterranean. The opportunity to obtain newfound wealth has added another twist to the Lebanon-Israel conflict. At the forefront of the Lebanese-Israeli Eastern Mediterranean dispute is over the rights to explore and exploit the newly discovered offshore natural resources. The primary focus for both sets of Governments is the coastal and Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) demarcation lines because adjustments to these lines will determine the amount of offshore oil and gas each State can access. This research follows a realist-geopolitical approach in order to analyze the dispute and the importance of the negotiation process while ending with some potential benefits of a permanent agreement on energy security for both Lebanon and Israel.

Introduction

This research paper focuses on the maritime territorial and border dispute, including the significance of the negotiation stage, that is taking place between Lebanon and Israel following the discovery of vast offshore natural resources. Lebanon and Israel have been in an official state of war since the first ‘Arab -Israeli Conflict in 1948-1949’ (Shibley 2016) with bleak prospects for a border solution on both land and sea. There have been several incidents of bloodshed that weakened the security condition at the Lebanese-Israeli border. One is ‘Operation Litany’: the 1978 Israeli invasion to destroy the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) south of the Litani River (Historical Security Council 2014). Another is the ‘1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon’ including of Beirut, which changed the security dynamics at the Lebanon-Israel border since it resulted in the expulsion of the PLO but the emergence of Hezbollah in its place. Furthermore, from 1985 to 2000 the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) along with the South Lebanon Army (SLA) controlled a ‘Security Zone’(Libel 2011):a vital geostrategic buffer region across the south Lebanese – north Israeli border and equivalent to 849.5 KM2/8.5% of Lebanon’s landmass (Luft 2000).

(The Economist1999)

The Obstruction of Both History and International Law

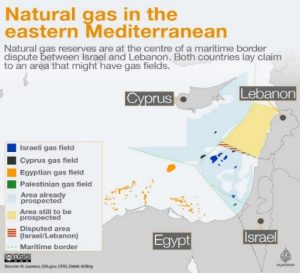

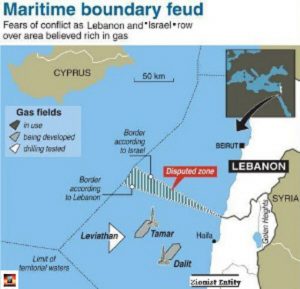

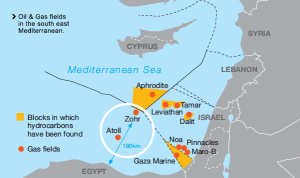

The Lebanon-Israel row has historically been restricted to a land dispute. However, the discovery and possibility of exploring and exploiting natural resources in the Eastern Mediterranean have brought to the forefront the unsettled maritime and EEZ borders that exist between the two tiny Middle East and Mediterranean nations. A discovery and novel issue that will likely be based on historical and contemporary trends be difficult to overcome due to a number of entrenched obstacles. First, Lebanon and Israel have been in an official state of war since 1948 which cripples efforts to negotiate a boundary accord (Kader 2012). This is especially the case regarding issues of contention such as the rights to explore and exploit offshore natural resources, which came to the forefront with the “discoveries of huge natural gas reserves off the coast of Haifa” (Kader 2012, p.79). Second, Lebanon’s refusal to recognize the existence of Israel prevents the application of legal methods of international law that could stimulate direct State to State negotiations: be it through arbitration, conciliation, or submitting the dispute to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. For example, applying international law specifically going through the process of direct negotiations could encourage Lebanon and Israel to sit down with Cyprus and negotiate (in a three-party discussion) “a triple point delimitation”. Such an agreement would in all probability solve the legal part of the dispute. However, “to avoid implicit recognition of Israel, Lebanon” ‘deliberately failed to define’ “a triple point delimitation between its own territorial waters, Cyprus and Israel” (Barrier and Ahmad 2018, p. 2). Moreover, while Lebanon and Israel could take their case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) which was created to resolve such disputes, Israel’s rejection of the ICJ’s jurisdiction weakens the latter’s ability to exercise and execute its authority (Barrier and Ahmad 2018) over the case. Third, Israel’s history of invading, violating, and occupying Lebanon’s land, sea, and air territories with the add imperialist claim that Lebanon is part of the ‘Promised Land’ (Horn 2000) also weaken the prospects that peaceful negotiations will be successful. Fourth, the 2000United Nations (UN) brokered ‘Blue Line’ established a land border but failed to create a maritime boundary(Kader 2012) – negligence and or oversight by the UN and previous Lebanese and Israeli Governments that has come to the forefront and been felt with the discovery of offshore Eastern Mediterranean oil and natural gas wealth.

(Al Jazeera 2017)

(Al Manar 2011)

Applying The Principles of International Law to The Dispute

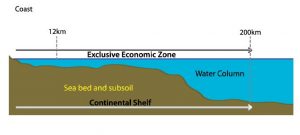

Both Lebanon and Israel have resorted to legal manipulations by adjusting their maritime border coordinates in order to obtain the legitimacy to claim an EEZ that encompasses the substantially discovered oil and natural gas reserves. However, this type of legal manipulation can be deterred by referring to international law specifically to certain United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) articles (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982). Therefore, in order to establish a well-rounded framework of the situation analysis of the key UNCLOS provisions to the dispute is recommended including each of the two States’ attitudes towards the Convention. Although only Lebanon is a party to UNCLOS having ratified it in 1995 (Wählisch 2011), Israel is nevertheless bound by certain provisions as they are recognized as international customary Law (Hamd et al. 2014). For example, in accordance with UNCLOS (1982), Article 3: Lebanon and Israel are allowed to extend their territorial seas up to 12 nautical miles from the baselines of their coasts. While UNCLOS Article 57 states that: Lebanon and Israel cannot expand their EEZs more than 200 nautical miles from the baselines of their territorial seas. In addition, another provision states “that, coastal States have sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring, exploiting, conserving and managing natural resources in the (their) EEZs” (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982, p. 44; Shibley 2016, p. 68).

(Debbas 2012a)

(De Micco 2014)

Furthermore, there are supplementary provisions of international law such as the International Court of Justice Statute Article 38 and UNCLOS Article 74 (UNCLOS 1982) which state that: because Lebanon and Israel have adjacent coasts, they are legally bound to demarcate their EEZs through the application of international law in order to reach a just resolution (Wählisch 2011). Additional international law articles and conditions also encourage a negotiated settlement. For example, the fact that Lebanon and Israel lie within 400 nautical miles of each other -they are per the clauses laid out in UNCLOS expected to agree on a settlement of their maritime frontiers (Shibley 2016). Another key UNCLOS provision is Article 123, Part IX which states that: because the “Mediterranean is a semi-enclosed” region: ‘in the face of discord, Israel and Lebanon are required to collaborate’ (Barrier and Ahmad 2018, p.2) – in this case with respect to their Eastern Mediterranean dispute.

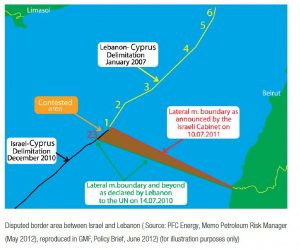

The Importance of Cartography

In July 2010, the Lebanese State submitted charts and geographical coordinates to the UN Secretary-General which indicated its view of the country’s maritime and EEZ boundaries. The charts and coordinates were drawn by Lebanese army cartographers and then reviewed and subsequently confirmed by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) in 2011 (Hamd et al. 2014). The charts and coordinates are based on the ‘Paulet-Newcombe and General Armistice Accords’ (Hamd et al. 2014; Kader 2011) and the ‘Manual On Technical Aspects of UNCLOS’(Kader 2011). The Government’s use of the ‘Paulet-Newcombe and Green Lines’ is very important to its geographical and legal maritime boundary defense. For example, Lebanon’s coastline stretches from north to south, from the Al Arida River to Ras Naqoura. Establishing the shoreline is key for two reasons. First, it is the point of reference for measuring nautical limits including for the EEZ. Second, it has a legal and geographical component whereby bilateral boundary accords are taken into consideration between neighboring States like Lebanon and Israel. As a result of this component: Lebanon’s EEZ stretches from coordinate point 7 north of the Al-Arida River southwards encompassing point 23 which is 133 KM from the southern coastal region of Ras Naqoura, marking the Lebanese-Israeli land boundary. Referring to the ‘Green Line’ maritime coordinates, the then Lebanese Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mansour sent an official letter to UN Secretary-General Benki Moon on June 20, 2011:

the southern maritime border extends from point B1 on the shore at Ra’s Naqurah, the first point on the 1949 Israeli-Lebanese General Armistice Agreement table of coordinates, to point 23, that is equidistant between the three countries concerned (Lebanon, Israel, and Cyprus), and on the coordinates of which all must agree (Hamd et al. 2014,p. 34).

(Debbas 2012b)

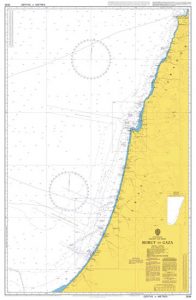

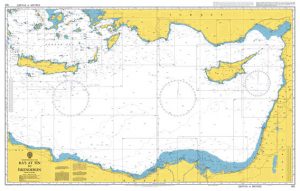

Furthermore, Lebanese officials relied on two charts that were drawn up by the UKHO: “the British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 2634 (Beirut to Gaza) and the British Admiralty Nautical Chart No.183 (Ra’s at Tin to Iskenderun)” (Kader 2011, p.5); as well Chart B-1 (the region of Naqourah) that was produced by the Office of Geographical Affairs of the Lebanese Armed Forces Command (Kader 2011) in order to provide the sources for delineating the baseline of Lebanon’s southern coast. Additionally, the Lebanese Government also referred to both the baseline of the south Lebanese coast and to UNCLOS (1982, p.30) Article 15 in order to try to prove that the southern limits of Lebanon’s EEZ: was “the median line equidistant from the nearest point on the baseline of Lebanon and Israel” (Kader 2011, p. 5). In fact, according to UNCLOS Article 15 (UNCLOS 1982) when two countries’ coasts are adjacent or opposite each other like is the case with Lebanon and Israel, then neither State is allowed to elongate its territorial sea beyond the median line, etc. Yet, there is a loophole, where it is plausible due to special circumstances (lack of clarity of their historic maritime borders) for Lebanon and Israel to alter the delineation of their respective maritime borders.

Chart I: British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 2634 (Beirut to Gaza)

(MARYLANDNAUTICAL 1983)

Chart II: British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 183 (Ra’s at Tin to Iskenderun)

(MARYLANDNAUTICAL 1969)

“List of Geographical Coordinates (Drawn up by the Lebanese National Defense)

for the delimitation of Lebanon’s Exclusive Economic Zone in WGS 84

The following tables contain position information on the Median Line between Lebanon and Israel/Palestine

All positions are referred to WGS 84 joined consecutively by geodesics

Southern Median Line (Lebanon – Israel/Palestine)”

| Points | Degrees | Minutes | Seconds | Degrees | Minutes | Seconds | ||

| 18 | 35 | 6 | 11.84 | E | 33 | 5 | 38.94 | N |

| 19 | 35 | 4 | 46.14 | E | 33 | 5 | 45.79 | N |

| 20 | 35 | 2 | 58.12 | E | 33 | 6 | 34.15 | N |

| 21 | 35 | 2 | 13.86 | E | 33 | 6 | 52.73 | N |

| 22 | 34 | 52 | 57.24 | E | 33 | 10 | 19.33 | N |

| 23 | 33 | 46 | 8.78 | E | 33 | 31 | 51.17 | N |

(Kader 2011)

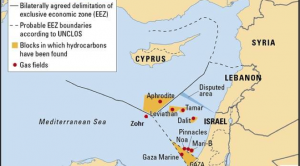

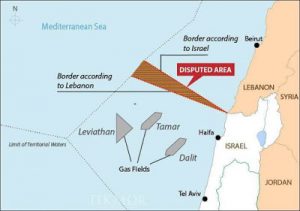

Israel and Lebanon’s Overlapping Maritime Coordinates

However, the coordinates that Israel claims for its maritime and EEZ borders overlap with Lebanon’s. Israel professes an EEZ border that starts at Ra’s Naqoura, which is 35 meters north of Lebanon’s preliminary coordinate and extends 127 KM to end at Point 1, which lies 17 KM northeast of point 23 on Lebanon’s EEZ (Hamd et al. 2014). Israel based its interpretation of its maritime border on the ‘Blue Line’ specifically the point on the border to which the IDF withdrew in 2000 (Minas and Diamond 2018). Israel’s demarcations created an overlapping ‘Zone’ of around 854 KM2, extending between points 1 and 23 on Lebanon’s EEZ (Hamd et al. 2014; Barrier and Ahmad 2018). Point 1 is especially important from a legal parlance since on the one hand, it “refers to the southernmost coordinate that was agreed to in the 2007 Lebanon-Cyprus” accord; and on the other hand, it is the starting point of a demarcated line agreed upon between Israel and Cyprus (Shibley 2016, p. 75).

In addition, when analyzing the maritime border situation between Lebanon and Israel it is important to include Cyprus’s maritime agreements with both countries. This is because Cyprus lies within 400 nautical miles of both Lebanon and Israel and therefore must be included in an overall agreement. Furthermore, any settlement involving Cyprus will have a direct bearing on the demarcation of the Lebanon-Israel maritime border. The reason why Cyprus’s offshore border agreements with both Lebanon and Israel affect a potential settlement between the latter two countries is due to Cyprus’s geographic proximity to both. Cyprus lies within 400 nautical miles of both Israel and Lebanon and as previously mentioned “when States lie within 400 nautical miles of each other, those States are expected to come to a mutual agreement” (Shibley 2016, p. 76). However, the much-disputed maritime coordinate point 1 between Lebanon and Israel has so far crippled that possibility. As a result of Lebanon and Israel’s respective and overlapping maritime and EEZ border accords with Cyprus, point 1 lies around 11 miles north of UNCLOS’s point 1. This 11-mile difference has as a consequence created a disputed 300 square mile region in the Eastern Mediterranean (Shibley 2016). One way of mitigating, diffusing, or even settling this problem is by referring to UNCLOS which implies that the maritime frontier between three nations such as that which exists between Lebanon, Israel and Cyprus “should be located at a point equidistant between” them (Shibley 2016, p.76).

(Micco 2014)

Based on the above analysis coastlines are an extremely important dimension to the Lebanese-Israeli maritime border relationship. Under Article 2 (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982): the sovereignty of coastal States, extends beyond their territorial lands and internal waters to the territorial sea . Furthermore, in accordance with provisions of UNCLOS: coastal nations have sovereign rights to explore, exploit, manage and conserve the natural resources within their EEZs (Wählisch 2011). In contrast to the Tamar and Leviathan fields which were discovered in Israel’s legitimate offshore waters, the later discovered Tanin and Karish fields were discovered in deep waters close to the disputed nautical ‘Zone’ between Lebanon and Israel. Yet, agreed rights to all four fields has not been settled (Barrier and Ahmad 2018; Hamd and et al. 2014).

(Elston 2015)

(Connection: The Vallourec Oil & Gas Magazine 2018)

The Principle of Domination Versus Freedom of The High Seas

Both Lebanon and Israel can exploit the Principle of Domination argument, which states that “ ‘the land dominates the sea’ ”, in order to back up their case (Jia 2014, p. 4). “It can be paraphrased as the domination of the territorial status and regime of the coast over the legal status and regime of the adjacent sea, including, where appropriate, the subjacent sea-bed and subsoil” (Jia 2014, p. 4). However, there are also limitations to using the Principle of Domination as a strong legal argument, since superior legal claims trump it. ‘For example, the general principle of the law of the sea specifically the freedom of the high seas limits a State’s ability to expand its territorial claims in the seas and oceans’ (Jia 2014, p. 31). The authority of the freedom of the high seas is derived from the international community’s commitment to preventing any State from achieving total control over the adjacent sea. This commitment has been endorsed and ratified by member states of the international community to the effect that it is now an integral part of the UN charted UNCLOS. According to UNCLOS Part VII, Section 1, Article 87 entitled the Freedom of the high seas, “the high seas are open to all States, whether coastal or landlocked. It comprises, inter alia, both for coastal and land-locked States: a) freedom of navigation; (b) freedom of overflight; (c) freedom to lay submarine cables and pipelines, subject to Part VI (of UNCLOS); d) freedom to construct artificial islands and other installations permitted under international law, subject to Part VI (of UNCLOS); e) freedom of fishing, subject to the conditions laid down in section 2, Part VI (of UNCLOS); f) freedom of scientific research, subject to Parts VI and XIII (of UNCLOS). These freedoms shall be exercised by all States with due regard for the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas, also with due regard for the rights under this Convention with respect to activities in the Area” (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 p. 57). Thus, if the international community pressures Lebanon and Israel to negotiate on their maritime borders within the confines of the provisions laid down in UNCLOS, which should be the primary document for dealing with such issues, then their respective maritime territorial and border claims would be restricted to the stipulations laid down by international law. This would mean that both States would have to negotiate from a more constrained position, but would also at the same time be negotiating from a more realistic-legal position. Therefore, it is assumed that UNCLOS specifically Article 87 should be used as the primary instrument of international law in any future Lebanese-Israeli maritime border and territorial negotiations.

(Reed and Soloman 2017)

In addition, the ICJ has also played a major role in the understanding of the land dominates the sea’ principle. For example, the ICJ links the ‘Principle of Domination’ theory to the concept of sovereignty. It places great importance on the notion of sovereignty as the starting point for governing maritime rights to which the coastal country is granted under international law. This can be seen in statements the Court made in 2002 and 2009. First, coastal States’ maritime rights are obtained from their sovereignty over territorial land; and second, the rights of nations to control an EEZ are founded on the concept, ‘the land dominates the sea’ (Jia 2014). The ICJ’s views on territorial sovereignty are very important in analyzing Lebanon and Israel’s land and maritime disputes. Therefore, taking the line of the ICJ: only a final settlement on the legal territorial status of the Sheba Farms and a conclusive agreement on the land borders through a definitive demarcation of the ‘Blue Line’ will the legitimacy and legality of Lebanon and Israel’s respective maritime including EEZ claims be recognized under international law.

(Bacci 2017)

Conclusion

It is difficult to argue against a bleak future regarding any resolution being reached with respect to the Lebanon-Israel oil and gas dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean. There have been nearly three-quarters of a century and counting of missed opportunities to settle on a demarcated boundary line that is mutually acceptable to both sides. Perhaps most frustrating is that both peoples are socially and structurally suited for establishing national borders. Lebanon is to a certain extent historically Western oriented due to some Western influences that go back a millennium and especially since the mid-19th Century. This connection helped create an Anglo-American-French-educated elite and at one stage a stable and large middle class, which should have (had) the ability to understand the mechanisms, machinations and value of forming State (International) borders. While the majority of Israel’s citizens come from the former empires and States of old Europe (pre-World War I and World War II) which have for hundreds of years since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia been organized within legally bound international borders under the concept of State sovereignty (Patton 2019). Therefore, both Lebanese and Israelis have either the theoretical and or practical knowledge and experience of living under State borders.

Yet, despite the constant setbacks to a viable settlement-the two countries have nevertheless, recommenced border negotiations. However, it took the discovery of hydrocarbon resources in the Eastern Mediterranean to push them to re-enter the negotiation stage on their disputed maritime and land territories and borders. This initiative has taken place under joint U.S. and UN auspices and mediation. In fact, the “demarcation of the maritime boundary between Lebanon and Israel” is essential if both sides want to secure their respective titles to Eastern Mediterranean oil and begin a phase of exploration and exploitation (Blank 2019). Moreover, a long-lasting and sustainable border and territorial agreement on the disputed land and maritime zones could resolve several unanswered questions between the two antagonists including:

1) a fair settlement of the oil and gas dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean,

2) the real possibility of the disarmament of Hezbollah’s militia wing since the primary basis of the Party’s claim to using arms is to resist Israel and liberate the Lebanese territories that the latter occupies

and

3) mutual recognition and acceptance of each nation’s respective international borders

In conclusion, perhaps the best way to sum up this research is through quoting the following passage: “the Lebanese-Israeli maritime border dispute in an area potentially rich in oil and gas perfectly embodies the entanglement between economic interests, geopolitical stakes” (Barrier and Ahmad 2018, p.1) and geostrategic considerations.

Writer Simon Nasr MA, King's College, University of London, UK.

References

- Al Manar (2011) Lebanon-Zionist Maritime Conflict Evolves. [Online]. Available from: https://archive.almanar.com.lb/english/article.php?id=28466

- Al Jazeera (2017) The Disputed gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean. [Online]. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/interactive/2017/03/disputed-gas-fields-eastern-mediterranean-170307170904483.html

- Bacci, A. (2017) Lebanon Launches Its Offshore Oil and Gas Sector. [Online]. Available from: http://www.alessandrobacci.com/2017/06/lebanon-launches-its-offshore-oil-gas-sector.html

- Connection: The Vallourec Oil & Gas Magazine (2018) In the south eastern Mediterranean Sea, 190 km off the Egyptian coast, on a drillship operating in water depth of 1,500 meters, Vallourec’s latest CLEANWELL®technology was successfully used by Petrobel* in the Zohr gas field, for running corrosion resistant alloy (CRA) pipes. [Online]. Available from: http://www.connection-mag.com/?p=5333

- Elston, L. (2012) East Med E&P unhindered by maritime dispute. [Online]. Available from: http://interfaxenergy.com/gasdaily/article/8393/exploration-for-east-mediterranean-gas-unhindered-by-maritime-dispute

- Elston, L. (2015) Endgame unclearfor Israel’s cartel regulators. [Online]. Available from: http://interfaxenergy.com/gasdaily/article/15361/endgame-unclear-for-israels-cartel-regulators

- Horn, C.B. (2000) Lebanon In The Holy Scriptures. The Journal of Maronite Studies [Online] 4(1) Available from: http://www.maronite-institute.org/MARI/JMS/january00/Lebanon_In_The_Holy_Scriptures.htm

- Jia, B.B. (2014) The Principle of the Domination of the Land over the Sea: A Historical Perspective on the Adaptability of the Law of the Sea to New Challenges. German Yearbook of International Law, [Online]57, pp 1-32. Available from: http://www.iilj.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/JiaIILJColloq2015.pdf

- Kader, N.A. (2012) Interviewed by Ramsbotham, A. (2012). Available from: https://www.c-r.org/accord-article/boundaries-and-demarcation-delimiting-and-securing-lebanon%E2%80%99s-borders

- Luft, G. (2000) Israel’s Security Zone in Lebanon – A Tragedy?.Middle East Quarterly [Online] 7(3) Available from: https://www.meforum.org/articles/other/israel-s-security-zone-in-lebanon-a-tragedy

- Libel, T. (2011) Crossing the Lebanese Swamp: Structural and Doctrinal Implications on the Israeli Defense Forces of Engagement in the Southern Lebanon Security Zone, 1985–2000. Marine Corps University Journal [Online] 2(1), pp 1-164. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/268388730_Crossing_the_Lebanese_Swamp_Structural_and_Doctrinal_Implications_on_the_Israeli_Defense_Forces_of_Engagement_in_the_Southern_Lebanon_Security_Zone_1985–2000

- MARYLANDNAUTICAL (1969) The British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 183 (Ra’s at Tin to Iskenderun). [Online]. Available from: https://mdnautical.com/np131-british-admiralty-chart-catalog-a2/6448-british-admiralty-nautical-chart-183-ra-s-at-tin-to-iskenderun.html

- MARYLANDNAUTICAL (1983) British Admiralty Nautical Chart No. 2634 (Beirut to Gaza), [Online]. Available from: https://mdnautical.com/f-eastern-mediterranean-sea-black-sea/8420-british-admiralty-nautical-chart-2634-beyrouth-beirut-to-gaza.html

- Minas, S. and Diamond, H.J. (2018) Stress Testing the Law of the Sea: Dispute Resolution, Disasters & Emerging Challenges. Leiden and Boston: A Law of the Sea Institute Publication.

- National Defense Magazine (2011) Potential Conflict Between Lebanon and Israel Over Oil and Gas Resources – A Lebanese Perspective, Lebanon: National Defense Magazine. Available from: https://www.lebarmy.gov.lb/en/content/potential-conflict-between-lebanon-and-israel-over-oil-and-gas-resources-%E2%80%93-lebanese

- Patton, S. (2019) The Peace of Westphalia and it Affects on International Relations, Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. The Histories[Online] 10 (1), pp 91-99. Available from https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1146&context=the_histories

- Reed, J. and Soloman, E. (2017) Israel and Lebanon clash over maritime border amid oil interest – Financial Times. [Online]. Available from: http://tekmormonitor.blogspot.com/2017/03/israel-and-lebanon-clash-over-maritime.html

- Shibley, A. (2016) Blessings and Curses: Israel and Lebanon’s Maritime Boundary Dispute in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. The Global Buisness Law Review [Online] 5(1), pp 50-80. Available from: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://www.google.com/&httpsredir=1&article=1053&context=gblr

- The Economist (1999) Time to leave the insecurity zone. [Online]. Availble from: https://www.economist.com/international/1999/05/27/time-to-leave-the-insecurity-zone

- The AUB Policy Institute (Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs) (2018) The Geopolitics of Oil and Gas Development in Lebanon. Beirut: The AUB Policy Institute (Issam Fares Institute for Public Policy and International Affairs, 1. Available from: https://website.aub.edu.lb/ifi/publications/Documents/policy_memos/2017-2018/20180121_geopolitics_oil_and_gas_lebanon.pdf

- United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1982) United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Montego Bay, Jamaica: UNCLOS. Available from: http://www.un.org/Depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf

- Wählisch, M. (2011) Israel-Lebanon Offshore Oil & Gas Dispute – Rules of International Maritime Law. American Society of International Law [Online] 15(31) Available from: https://www.asil.org/insights/volume/15/issue/31/israel-lebanon-offshore-oil-gas-dispute-%E2%80%93-rules-international-maritime