ABSTRACT

India and China are two of the oldest living civilizations of the world with numerous similarities and associations. The exchange of ideas between the two countries has been like a flowing river, sometimes it runs smoothly but sometimes there are hurdles but it has always kept flowing incessantly. Despite the similarities, both the countries have traversed different political and social paths. India and China share a loosely demarcated border and have come face to face multiple times on the Line of Actual Control (LAC), the de facto border between the two countries after the 1962 Sino-Indian War. In the last 50 years, both countries have squabbled over territorial demarcations all along the India- China border. There are many places in the Ladakh area, near the Bhutan-China border, and in Arunachal Pradesh where the two countries differ over the actual on-ground position of the LAC. The Doklam dispute (2017), Daulat Beg Oldi and Chumar (2013), and the Demchok (2014) dispute are examples of clashes in the congested boundary region. The current crisis in the Galwan Valley and Pangong lake area in the Ladakh region and at the Nathu La pass near the Bhutan-China border has once again highlighted the volatility of India-China relations.

The Background of Dispute

Understanding this volatile nature of border conflict requires an exploration of various factors, like the geopolitical realities in Asia, the historical legacies in bilateral ties, trade and other economic interests, domestic politics in both countries, and the pursuit of common global concerns. Various dispute resolution mechanisms are already in place and both countries have actively resorted to these existing mechanisms to resolve conflicts in a peaceful manner. After almost two years and numerous rounds of deliberations and negotiations, the Galwan Valley issue is at a stalemate.

This article aims to fulfill the following:

- To trace the colonial linkages of the long withstanding border conflict between India and China in the Western Sector

- To map out the evolution of disputes and analyse the changing nature of boundary disputes between India and China

- To examine the use of dialogue and negotiations by India, China and explore its limitations

- To look at the present-day conflict of Galwan Valley for analyzing the contours of conflict and assessing future repercussions

Traditional Boundaries

Throughout history, the neighboring Asian giants, India and China had coexisted peacefully under different dynasties and rulers. For centuries, traders, travelers and preachers, had crisscrossed the seemingly impassable mountain ranges along well-established trade routes. The birth of India and China as nation-states commenced the process of political consolidation of their territories. Since boundaries are the first expressions of a modern state, efforts were made to define and delimit a linear boundary between India and China in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and their previously ignored far-flung frontiers started to be formalized as boundaries. After liberation, the People’s Republic of China (PRC), renounced all the previous border treaties and agreements as ‘unequal’ and belonging to the ‘century of humiliation’. It then started a fresh process of renegotiating and redrawing boundaries. On the contrary, India considered a boundary to be a ‘historical demarcation’ which has been recognized by tradition and customs for centuries and there is no necessity to demarcate it again.

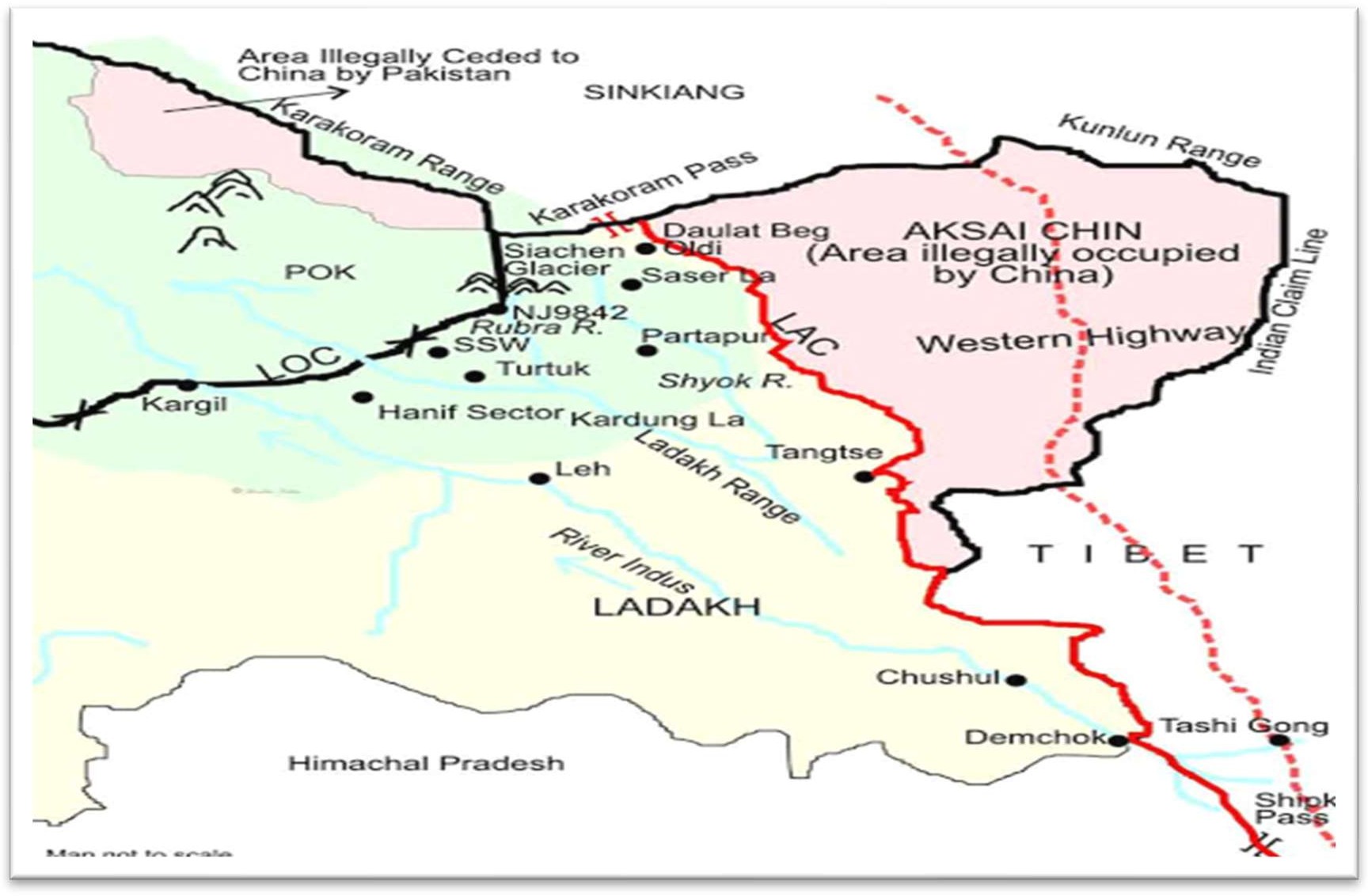

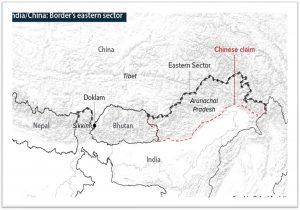

The India–China boundary is usually trifurcated into three segments– the Western Sector (covering proximate areas of the Ladakh region of Jammu and Kashmir with Tibet, and also the segment which technically is now Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, with Xinjiang); the Middle Sector (proximate areas of Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh with Tibet); and the Eastern Sector (the proximate areas of Arunachal Pradesh with Tibet) However, the pivotal disputed territories are Aksai Chin in the west and Arunachal Pradesh in the east.

Western Sector of India

Source: http://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/dbo-indias-response-and-defence-preparedness/

Eastern Sector of India

Source: https://dailybrief.oxan.com/Analysis/GI253477/India-China-Borders-eastern-sector

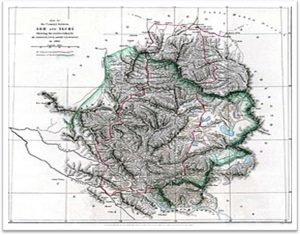

India’s claim to the Aksai Chin area is largely based on the Johnson Line. In 1846, Great Britain annexed Kashmir which helped the British to secure the northern frontier of India. In 1856, W.H. Johnson, a civil servant with the Survey of India, was sent to survey the area and he proposed the ‘Johnson Line’, putting Aksai Chin in Kashmir. Even though Aksai Chin is an uninhabited barren plateau, it is of high strategic value to China as it is an important passage point between Tibet and Xinjiang [XUAR]. The McMahon Line in the Eastern sector serves as the legitimate border of India, which was part of the 1914 Simla Convention between British India and Tibet, without the agreement of China. Competing claims are based on historical records, administrative controls, cultural linkages, etc. China refuses to accept Indian claims, calling them based on the days of the British Raj, and India does not accept Chinese claims based on their obscure and inconclusive imperial controls.

Johnson Line marked in dark green

Source: https://www.wikiwand.com/en/Johnson_Line_(boundary)

Dispute Resolution—Agreements and Initiatives Undertaken by India and China

After the 1962 war, both the countries came up with a loosely demarcated LAC (Line of Actual Control), though it has never been demarcated and the Indian understanding of LAC varies significantly from the Chinese. Both India and China consider Aksai Chin to be a part of their territory since they follow a different line of control but in 1993 PM Narasimha Rao agreed to maintain peace along the LAC which separates Jammu and Kashmir from Aksai Chin.

Various rounds of border talks and confidence-building measures (CBM’s) were undertaken and the creation of a Joint Working Group after Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to China was perhaps the most serious attempt to resolve the border conflict on the principle of mutual understanding and accommodation. Various bilateral treaties were also signed in the years, 1993, 1996, 2005, 2012, 2013 regarding border defense cooperation. All these initiatives were measures to maintain stability on the border rather than come to a conclusion of a properly demarcated border. Prime Minister Modi and the Chinese President Xi Jinping have participated in informal summits in April 2018 in Wuhan and at Mamallapuram in 2019, with a focus on further broadening the bilateral ties and to strengthen communications so that they can build trust and understanding.

Present Conflict—the Case of Galwan Valley

In June, Chinese and Indian soldiers clashed in the Galwan Valley in Eastern Ladakh. The close-combat skirmish resulted in more than twenty deaths on the Indian side and an unknown number of Chinese casualties. This was the bloodiest fight along the disputed Sino- Indian boundary in over four decades and has changed the India- China relationship irrevocably. China labels the military standoffs as pre-emptive measures in response to the Darbuk-Shyok- Daulat Beg Oldi Road infrastructure project in Ladakh and the revocation of the special status of Jammu and Kashmir. For years, PRC has enjoyed better infrastructure near the LAC and it wasn’t until 2005 that India announced a project of 61 roads covering about 3400 kilometers near the LAC. The most important of these, the Darbuk-Shyok-DBO Road was completed in 2019 and is quite close to the Galwan Valley, where the incident took place.

On the Indian side, these developments have brought into question the good faith and intent of the PRC in resolving outstanding issues and have given birth to reservations regarding the various agreements and rules of engagement that have since decades, guided behavior along the border.

The Chinese behavior in Eastern Ladakh has been both coercive and intimidating, leaving few measures short of military escalation for India to find a way back to the status quo ante. The Belt and Road Initiative in general, and the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor in particular, has been interpreted as an attempt to encircle India.

Analysts have linked these border tensions to Chinese assertiveness as this could be seen as China’s desire to bring India down and show its military might amidst the Covid-19 pandemic, which damaged the Chinese economy and international reputation. Further, the present leadership of Xi Jinping resorts to wolf warrior diplomacy and prefers to be more practical and militarily assertive.

Currently, both sides are focusing on strengthening communication channels at various levels. The circulars issued by the Indian and Chinese Foreign Ministries demonstrate that both parties agree on the necessity to disengage but there is still much to cover on ground. New Delhi and Beijing hold very different views of what happened the night of June 15 in the Galwan Valley. India pointed to “premeditated” Chinese action that “reflected an intent to change the facts on the ground in violation of all our agreements to not change the status quo”. China said that “Indian frontline border forces openly broke the consensus reached.”

Prime Minister Modi said in his June 17, 2020 address that India’s “sovereignty is supreme”, and Foreign Minister, S. Jaishankar has also specified that “it cannot be business as usual with Beijing as long as there is a border stand-off.” As indicated by the stance of both the governments, we see that there has been a mutual trust deficit between both the governments. The Galwan Valley incident can’t be viewed in isolation as it is yet another tectonic outburst produced due to the geopolitical history, bilateral ties, and border conflict between the two nations.

Way Forward

Today, after almost two years, the stalemate is still continuing. There have been numerous rounds of border talks but they have not led to fruition. The process of disengagement along the LAC remains unfinished and the path forward is riddled with mistrust and suspicion. Non-military policy options have been explored, like the banning of around a hundred Chinese apps and a blanket call of boycott of Chinese products has gained some mass appeal in India.

The relationship between Asia’s two giants continues to be marred by the unresolved border dispute and the recent standoff has undeniably undone decades of painstakingly negotiated confidence-building mechanisms. But detailed protocols are already in place for troops to handle such face-off incidents. Both the countries are willing to access existing channels of communication and the border debacles do not escalate to full-blown wars. Due to increasing interdependence on one another, armed intervention seems as an unlikely possibility as any sort of armed conflict will lead to heavy costs across all spheres.

The border is fundamental to the relationship between India, China and until a mutually acceptable consensus is reached, the stalemate in the Himalayas will likely continue. Though, at the regional level, Delhi and Beijing have been involved in a complex strategic rivalry, neither of the states has allowed the bilateral ties to be hijacked by border disputes alone. The use of existing mechanisms to resolve the border standoff is a positive indication towards nonviolent resolution of conflicts. India and China realize that they share many common interests at the bilateral, regional, and global levels, so border disputes which emerge due to geopolitical histories will ideally not come in the way of tangible and long-term common interests.

Riya Shah is currently in her final year of Bachelors in Chinese at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She is passionate about conducting extensive, multi-domain China-focused research. Her areas of research interest include international relations, Chinese foreign policy and geopolitics of the East Asian region.

Author

Riya Shah is currently in her final year of her bachelor’s in Chinese at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. She is passionate about conducting extensive, multi-domain China-focused research. Her areas of research interest include international relations, Chinese foreign policy, and the geopolitics of the East Asian region.

REFERENCES

- Ayres, Alyssa. “The China-India Border Dispute: What to Know.” Council on Foreign Relations, Council on Foreign Relations, 18 June 2020,https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/china-india-border-dispute-what-know

- Basu, Nayanima. “’Most Difficult Phase’ – Jaishankar Says India-China Ties ‘Significantly Damaged’ This Year.” ThePrint, 9 Dec. 2020,https://theprint.in/diplomacy/most-difficult-phase-jaishankar-says-india-china-ties-significantly-damaged-this-year/563425/

- Chakravarti, P. C. India-China Relations. K.L. Mukhopadhyay, 1961.

- Dalvi, A. S. “India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector”, Savitribai Phule Pune University, 1995,http://hdl.handle.net/10603/161663

- Deepak, B.R. “China Won’t Accept Status Quo Ante.” The Sunday Guardian Live, 4 July 2020, 8:52 pm,sundayguardianlive.com/opinion/china-wont-accept-status-quo-ante.

- Deepak, B.R. “India Has Always Been in China’s Strategic Calculus.” The Sunday Guardian Live, 18 July 2020, 10:01 pm,sundayguardianlive.com/opinion/india-

always-chinas-strategic-calculus.

- Deepak, B.R. “India’s Myopic China Policy Needs to Change.” The Sunday Guardian Live, 11 July 2020, 10:54pm,sundayguardianlive.com/opinion/indias-myopic-china-policy-needs-change.

- “Fantasy Frontiers.” The Economist, The Economist Newspaper,2012,

www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2012/02/08/fantasy-frontiers.

- Gokhale, Vijay. “The Road from Galwan: The Future of India-China Relations.” Carnegie India, 10 Mar. 2021, org/2021/03/10/road-from-galwan-future-of-india-china-relations-pub-84019.

- Government of India. “Lok Sabha Debates” Vol-2 19531. Cols2231-2240.

- Hongzhou, Zhang, and Li Mingjiang. SINO‐INDIAN BORDER DISPUTES. June2013, ispionline.it/sites/default/files/pubblicazioni/analysis_181_2013.pdf.

- Hongzhou, Zhang, and Li Mingjiang. “China and Transboundary Water Politics in Asia.” 2017,doi:10.4324/9781315162973.

- “India-China Relations after Clashes in Ladakh: Looking for a New Modus Vivendi.” The National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR), 14 July 2020,nbr.org/publication/india-china-relations-after-clashes-in-ladakh-looking-for-a-new-modus-vivendi/.

- Karackattu, Joe Thomas. “India–China Border Dispute: Boundary-Making and Shaping of Material Realities from the Mid-Nineteenth to Mid-Twentieth Century.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, vol. 28, no. 1, 2017, pp. 135–159., doi:10.1017/s1356186317000281.

- Panda, Ankit. “Why the ‘Old Normal’ Along the Sino-Indian Border Can No Longer Stand.” The Diplomat, 10 July 2020. https://thediplomat.com/2020/07/why-the-old-normal-along-the-sino-indian-border-can-no-longer-stand

- Peri, Dinakar. “A Year after Galwan Clash, China Beefing up Positions along Lac.” The Hindu, The Hindu, 14 June 2021, thehindu.com/news/national/a-year-after-galwan-clash-china-beefing-up-positions-along-lac/article34806645.ece.

- Sali, M. L. India-China Border Dispute: A Case Study of the Eastern Sector. A.P.H. Pub. Corp., 1998.

- Scott, David. “Sino- Indian Territorial Issues: The ‘Razor’s Edge.’” The Rise of China: Implications for India, Cambridge University Press,2011.

- Shah, B. L. “CONFLICT RESOLUTION IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THE INDO-CHINA CROSS BORDER DISPUTE IN ARUNACHAL PRADESH.” The Indian Journal of Political Science, vol. 71, no. 2, Indian Political Science Association, 2010, pp. 599–611, http://www.jstor.org/stable/42753721.

- Shapoo, Sajid Farid. “The China-India Standoff and the Myth of a New Cold War.” The Diplomat, 13 June 2020,https://thediplomat.com/2020/06/the-china-india-standoff-and-the-myth-of-a-new-cold-war/

- Shrivastava, V. K. “Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute and Indo-Centric Reflections on China’s Military Capabilities, Thoughts and Options in the Near Future.”Vivekananda International Foundation, 9 Jan. 2017, vifindia.org/monograph/2016/december/20/sino-indian-boundary-dispute-and-indo-centric-reflections-on-china-s-military-capabilities.

- “Sino-Indian Border Dispute.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 16 Aug.2020, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sino-Indian_border_dispute.

- Taoqeer, Hamzah. “Gray Zone Conflicts in Asia Pacific.” Modern Diplomacy, 3Aug.2020,https://moderndiplomacy.eu/2020/08/04/gray-zone-conflicts-in-asia-pacific/

- Tripathi, Ashutosh. “’Disengagement Process along LAC Not Yet Complete’: India Rebuts China.” Hindustan Times, 30 July 2020,hindustantimes.com/india-

news/disengagement-process-along-lac-not-yet-complete-india-rebuts-china/story-

NpYy0IRVdhMBg11OANuNJJ.html.

- Varma, Gangesh Sreekumar. “Reading Between the Lines.” Fair Observer, 21 May2014,fairobserver.com/region/central_south_asia/reading-between-lines/.